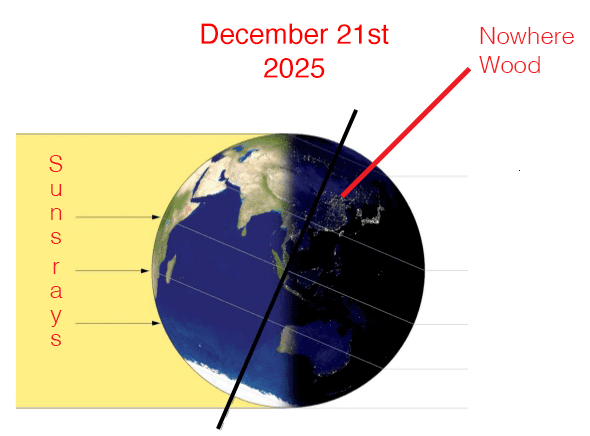

Some of the trees in Trendlewood Park play host to mistletoe, an ancient plant with mythological powers. Mistletoe is easiest to see in winter. when the trees have given up their leaves.

When older trees stand bare against the low sky, mistletoe hangs in their branches like dark thoughts. From the ground it looks an accident: round, self-contained worlds lodged high in the branches like lost balloons. Neither leafless nor quite at home.

In fact, evolution has shaped mistletoe into a highly effective machine for stealing space and water from mature trees. Firstly, there are separate male and female plants, each bearing flowers that produce pollen and fruits, respectively.

These are the female flowers, with their orange stigmas that catch pollen carried by late winter insects in February–March. These early insects are attracted by scent rather than colour. As a reward, the insects receive precious food, at a time when few other nectar foods are available. The seed is held inside a white translucent globe, that is the fruit.

The seed inside is wrapped in viscin, a gluey substance that stretches into threads when pulled apart. Mistle thrushes, blackcaps, and other winter birds gorge on the pearly berries when little else is available.

Birds wipe the sticky remains from their bills onto a branch, or pass the seed whole, leaving it stuck to the bark like a stain. There it waits, fixed fast against rain and frost, until spring warmth draws it into life. Germination begins not with invasion but with patience.

Mistletoe does not grow on a tree so much as into it. Its seeds, carried there by birds, germinate where they land and push a root-like structure—called a haustorium—through the bark and into the living wood.

From there it draws water and mineral salts from its host, tapping the tree’s transport system while still making its own sugars by photosynthesis. It is a hemiparasite: dependent, but not helpless; taking, but also growing greenly on its own account. The host tree bears the cost quietly, ring by ring, while the mistletoe thickens above, each year adding another fork to its slow, spherical architecture.

Gradually, over decades, the tree weakens and will eventually fail, as it plays host to more and more uninvited guests.

Despite this quiet parasitism, mistletoe gives generously to the wood. Its evergreen leaves offer shelter in winter; its flowers feed early insects; its berries are a crucial cold-season resource for birds. In Trendlewood Park, the thrush that guards a mistletoe clump does so fiercely, chasing off rivals with sharp calls and sudden wingbeats. The plant becomes a defended territory, a winter larder, a node of life when the rest of the canopy is stripped to essentials.

Long before botanists described haustoria and hemiparasites, mistletoe had already rooted itself in British imagination. To the Druids, it was a plant apart, especially when found on oak, rare and therefore potent. Pliny the Elder described how it was cut with a golden sickle and caught in a white cloth so that it never touched the ground, as if earth itself might dilute its power. It was associated with fertility, protection, and the suspension of ordinary rules—a plant that belonged neither fully to sky nor soil, growing between worlds.

That sense of being between has never quite left it. Mistletoe grows easily upon apple trees, and in orchards it has a magical significance. Cut on New Year’s Eve and hung in houses, it provides protections against witches and goblins. The old branch, taken down on New Year’s Eve must be burnt.

Hung in gloomy houses at bleak midwinter, mistletoe became a licence for closeness, an excuse for kissing when the year is at its darkest. The custom is gentler than the old rituals but carries the same implication: that life persists, that green things endure, that intimacy and renewal are possible even now.

In Nowhere Wood, when the light is low and the paths are slick with fallen leaves, the mistletoe bough watches from above, evergreen and unapologetic. It lives by taking, but also by giving—food, shelter, stories. It reminds the trees, and those who walk beneath them, that survival is always a matter of connection, and that even the strangest relationships can bind a landscape together.

Happy New Year from Nowhere Wood.

- Summarise how the mistletoe plant makes seeds and how these seeds are spread to new trees

![Bracket fungus on the old beech tree in Nowhere Wood. [Photograph: Pat Gilbert]](https://blog.neilingram.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/c1ab4241-025b-4d19-bc0d-1c0166ed0e24-1024x461.jpg)

![Yeasts and other fungi on fallen apples in Tendlewood Park. [Photograph: Neil Ingram]](https://blog.neilingram.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/IMG_4147-2-1024x768.jpg)

Let’s travel back in time three hundred years or more, to the East End Farm, near the hamlet of Nowhere.

Let’s travel back in time three hundred years or more, to the East End Farm, near the hamlet of Nowhere.