Nowhere Wood in late winter is a place of bare branches, weak shadowy light and unspoken secrets, waiting for new leaves start to emerge.

On the woodland floor, hidden beneath the shade of hazel and hawthorn, something strange is happening. By April, it is fully revealed.

It’s not flashy, no pretty flower show. Just a apple-green leaf, twisted like a bishop’s cowl. A greenish-purple hood half-hiding something inside. You’d walk past it if you didn’t know better.

The plant is Arum maculatum, but no one calls it that around here. It has lots of ancient names, some of which are so rude that they would make Geoffrey Chaucer blush! In Somerset, it was called ‘Adam and Eve’, but most places call it Lords and Ladies, and there’s a good reason for that. With a little imagination, we can see the tall upright lord dancing with his lady in the flowing green gown.

This is a flower and it is a seed making factory. It does this by subterfuge, luring insects and holding them hostage until it gets what it wants.

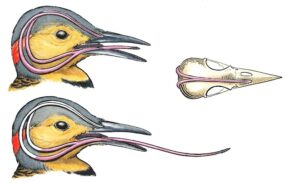

One glance inside the sheath and you’ll see the machinery of the deception: “the Lord” is called a spadix, sitting on top of a ring of yellow hairs that point downwards. Below them are the orange ovaries, that will become fruits containing the new seeds. These are the “Ladies”.

Beneath the ladies are the yellow pollen-making anthers, that ripen after the ovaries have received pollen from insects.

Down in the gloom of the woodland floor, the spadix heats up, becoming warmer than the air around it, which attracts small insects. It also gives off a smell of rotting meat and dung — irresistible, if you’re a midge or a small fly looking for a good meal.

They blunder in, hunting decay. Down they fall, past a ring of slippery hairs that trap them in the chamber below. There’s no nectar. No reward. But while they wander round, they give up their pollen to the ovaries. The pollen grows tubes that towards the egg cells, fertilising them, and making new seeds.

The stamens burst open with fresh pollen, which give the insects a quick meal, whilst covering their bodies in pollen.

The yellow hairs of the jail bars have withered overnight, allowing the insects to escape with their pollen load. No harm done, the insects immediately carry the pollen away to the next ripe lords and ladies flower in the wood.

![lords and ladies fruits, nowhere Wood, June. [Photograph: Neil Ingram]](https://blog.neilingram.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/IMG_3322-768x1024.jpeg)

By June. the sheath is long gone. But what remains is a spike of fruits, ready to ripen in the late summer sun. As bright as traffic lights, the fruits rise like a warning from the shade. Poisonous, yes. But beautiful.

The autumn is a time for making food, using its large leaves that are designed to capture the dim light of the woodland floor. The food is stored underground in a rhizome.

Later, the leaves disappear and the plant lives underground for the winter.

It lives on as a secretive rhizome, sleeping through the summer heat and the turning year, until — just as the bluebells fade — it returns to play its part again.

- Each ripe red fruit contains a seed of the Lords and Ladies plant. Birds, like thrushes and backbirds love to eat these fruits. Explain how this helps to disperse the seeds away from the parent plant.

- What are the advantages to small insects of going inside a Lord and Ladies flower?

It is late February, the cold weather has moved away and the frogs have moved back in. It’s been a couple of years since they were last here, but here are their newly-laid eggs and the female is hiding beneath the leaf in the top left corner of the photograph. What is a frog and how is it having adventures in Nowhere Wood?

It is late February, the cold weather has moved away and the frogs have moved back in. It’s been a couple of years since they were last here, but here are their newly-laid eggs and the female is hiding beneath the leaf in the top left corner of the photograph. What is a frog and how is it having adventures in Nowhere Wood?