It is a January morning, misty and still. The air hangs silently in Nowhere Wood. Suddenly close, but just out of sight, a loud and fast drumming shakes the stillness. Then a silent pause, followed by a quieter drumming coming from the other end of the wood.

Let’s find the first drummer. He’s hard to see, high up in the tree, but there he is, pressed against the tree trunk: a male great spotted woodpecker. The other drummer in the distance is a young female. The woodpeckers are having an adventure in Nowhere Wood.

Our male is digging a hole in his tree, hoping to impress the female. If it works, she will lay their eggs in the hollow space in the tree. This photograph, taken a few weeks later in Nowhere Wood, shows the new mother feeding her fledgling chick.

How can these woodpeckers drill such large holes in trees without injuring themselves? Well, it looks as if all parts of their bodies have special characteristics that enable the birds to do this. Scientists call these special characteristics, adaptations.

Look at this video of a great spotted woodpecker pecking at a tree. Look at his feet. He has three toes on each foot, with two toes facing forwards to grip and hold onto the tree trunk. This prevents him falling off when he pecks the tree! The beak is made of a tough material that keeps growing and keeps the beak sharp.

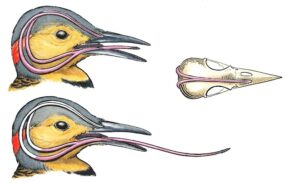

His skull is especially strengthened, like a builder’s hard hat. The brain presses right up against it and cannot move around.

The tongue extends backwards into the head as a long thin tube of bone and cartilage that runs right round the inside of the skull of the woodpecker. This acts like a seat belt, holding the brain in place.

The tongue is especially long and sticky, so it can go right into the tree holes, searching for insects.

The eyes fit tightly inside the skull, and do not vibrate whilst the bird is pecking. Their eyes have a special transparent membrane that closes across the front of the eye to prevent splinters of wood scratching the eyes. The feathers around the eyes and beak also stop wood reaching the eyes. Together, they act as safety spectacles!

Finally, a woodpecker is quite vulnerable to attack by larger birds when it is drumming against the tree. The patterns of lines and stripes act like a camouflage jacket, making the bird hard to see against the tree surface.

- Woodpeckers have a lot of adaptations to help them to survive in Nowhere Wood. This story contains a photograph that suggests that the woodpeckers are living successfully here. What does the photograph tells us about the future of woodpeckers in Nowhere Wood?

- Woodpeckers have developed these adaptations through evolution. Charles Darwin is the scientist who first suggested a possible way evolution could happen. This is called natural selection. Find out what natural selection is.

A different kind of woodpecker